(Pattie and Nicki in this picture from November)

Miracles.

Mom said, “You need to write about the miracle. Write about the miracle. You girls received a miracle. You got a miracle!”

What a word. But I had one - in November. I was walking around Lakeshore Park in Knoxville in the bright November sunshine, thinking - I’ve had a miracle. I’m not a person who gets a miracle. How did I get this miracle? I’m a person who slogs, slushes, slugs forth, white-knuckles, breaks, keens, rages, little faith, the works - but I was awash in the lightness of this miracle.

Was I allowed a miracle?

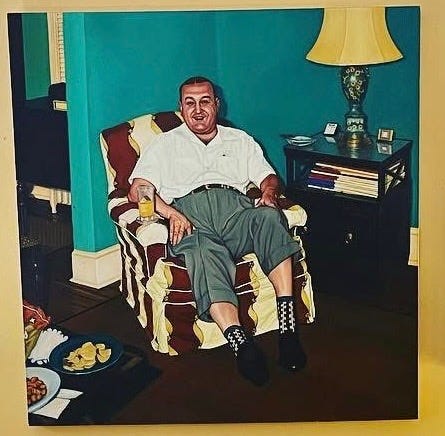

I have a long and winding history with Knoxville, specifically with this geographic spot in Knoxville, because of where my younger siblings attended school - Sacred Heart - right down the road. (Here is a road-trip picture to Sacred Heart in the fall with Mom and my brother, Duffy.)

Sixteenth Birthday

The day I turned sixteen, my mother took me for a driver’s test and I passed and then she handed me the keys and said, “Go pick up your brothers from football practice! Drive safe! Don’t wreck. Our insurance will skyrocket.”

One brother was at one practice in Cedar Bluff and the other was at football practice on Magnolia in East Knoxville. If you know Knoxville, you know they were nowhere near each other, but I picked up both brothers without incident, and I loved it. I loved the freedom of driving and blasting the radio without anyone telling me to “TURN IT DOWN.”

Mom, an elementary school music teacher, didn’t like loud music and often said, “Two minutes of peace is all I ask” with a cool washcloth over her eyes on the couch after a day of corraling kids into singing songs. My favorite story is when the tough kids in Detroit changed the words in the song“Old Dan Tucker” to “Old Dumb Fucker.”

But the day I got my license in Knoxville, Mom was thrilled to have a newly minted driver in the family. Dad could not help with the driving as he was a busy UT Vols football coach on the road recruiting or at the football office. He’d even hired a football player to teach me to drive, since my mother screamed, “OH JESUS” every time I barely touched the gas pedal.

In my mind, I see my mom doing cartwheels across the DMV parking lot, which did NOT happen. But she was overjoyed that I’d passed and could help her with the driving. She used to give me a blank check to do the grocery shopping at Winn Dixie and instructed me to buy the “five loaves for a dollar” Winn Dixie brand of bread, which she’d freeze to have extra on hand. Assistant football coaches made no money in those days, so things were on a tight budget.

I was probably driving a UT coaching car. The coaches were always given cars to drive around, so I was driving Dad’s since he was at the football office and didn’t need it. He would often spend 12-16 hour days at the football office.

Gold Duster

At seventeen, I inherited a Gold Duster under tragic circumstances. My uncle, a brilliant young artist, took his life in that car at the age of 22 in Washington DC after graduating from Notre Dame six months earlier. Still, my practical Irish Catholic family grieved (“pray for his soul and say some Hail Marys”) and gave me the car because I was the oldest cousin and the only one with a driver’s license and a car was a car.

Uncle Lefty, the middle brother between my father and Michael, said when I protested, “It’s what Michael would have wanted. Kerry, you need to take the car. It’s your car now.”

My grandfather, a man we called “Daddy Dear” (I know), had given Michael the car, four years earlier. I remember Michael driving us around DC blasting “Proud Mary” to celebrate his new set of wheels, and I kept hearing the Gold Duster Jingle playing on TV and now Michael had his own Gold Duster, which he drove back and forth to Notre Dame.

Dad agreed with Uncle Lefty, drove Michael’s car from DC to Knoxville, and gave it to me.

I dreaded seeing it again, but Dad said, “Hell, it’s a good car. Take it out for a drive. Get used to it. “ So I drove it around alone for the first time one evening in Knoxville, and it still had Michael’s Steely Dan 8-track tapes, papers, pens, and notes - I drove the car alone, trying to find Michael in the Gold Duster, but I heard nothing.

I asked, “Why?” And “Where are you, Michael?”

Nothing. No ghosts were in that car. But I still felt him all around me. Michael. What did we miss? What couldn’t we see? Why?

Then I eventually buried the idea of it being Michael’s car until I wrote about it all in my first novel, Offsides, to atone for being so clueless at seventeen to Michael’s pain and the tremendous loss of him.

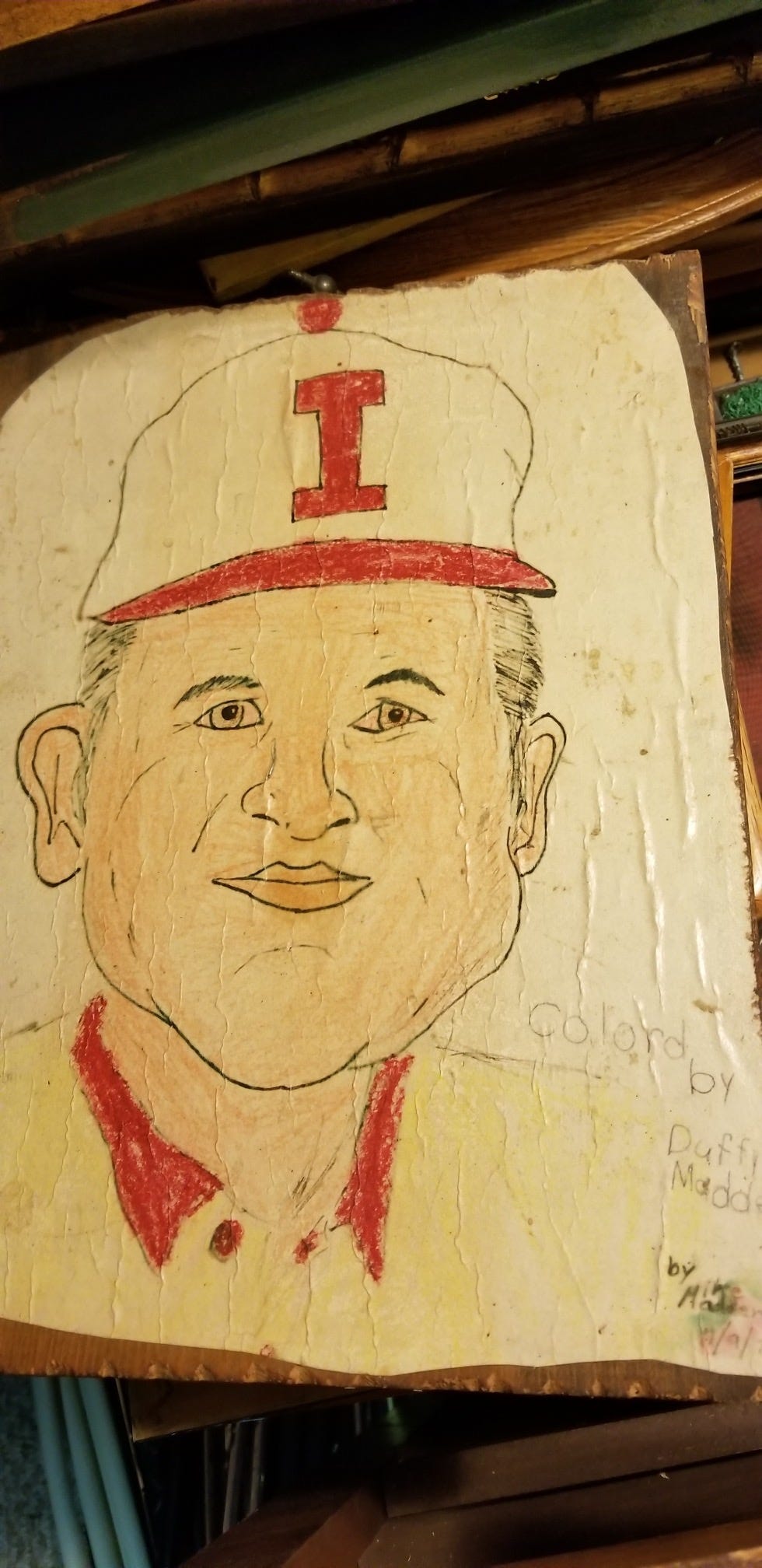

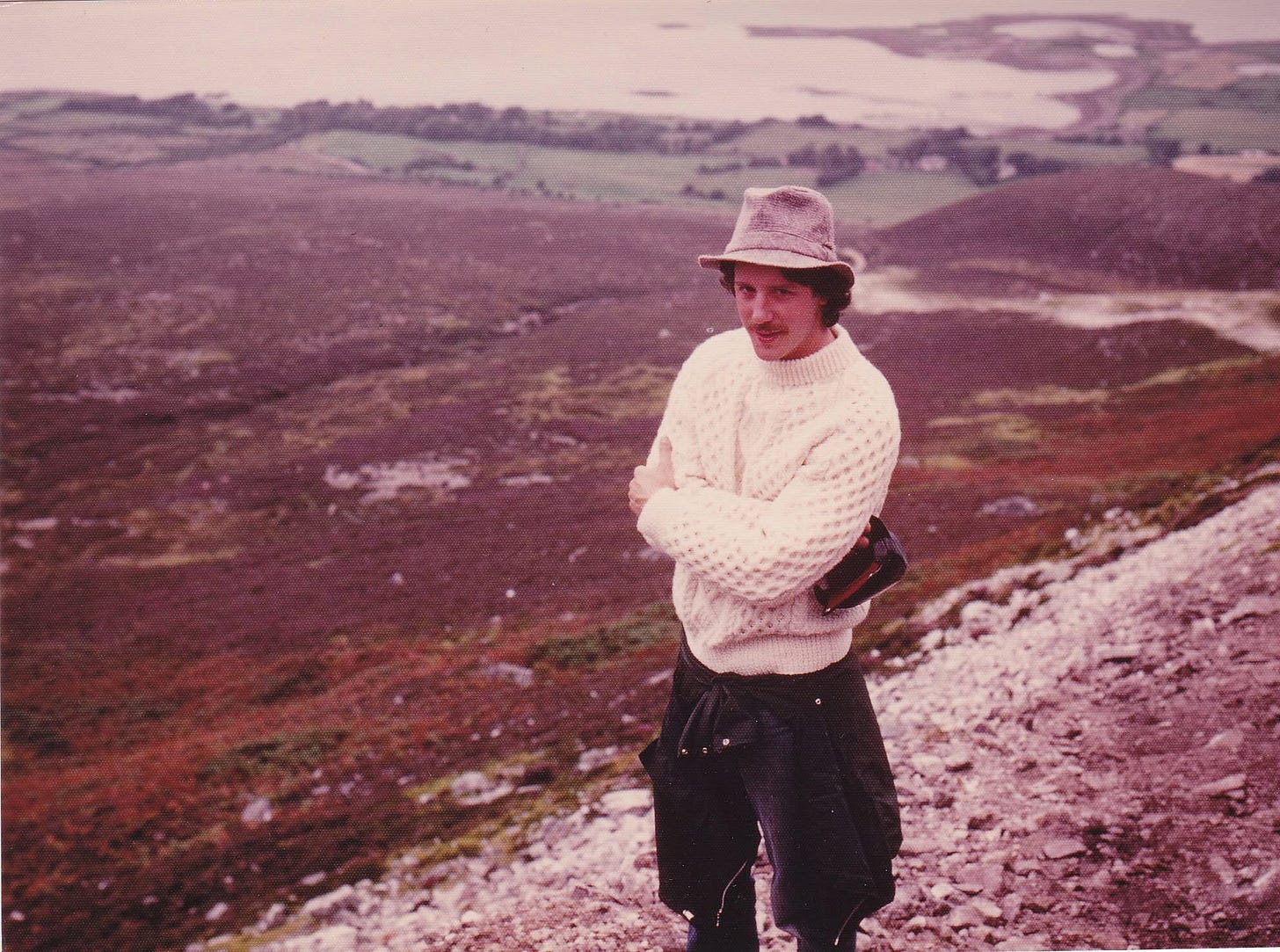

(Michael Madden in Ireland, and above is his senior painting from Notre Dame as an art major along with a picture of Coach Johnny Majors at Iowa State that Michael drew as a teenager that my brother, Duffy, colored in as a little boy. Coach Majors’ son, whom we called “Little John” for years gave us this picture of this ancient artwork from Ames, Iowa in the fall while on the road trip.)

Family Chauffeur

It became my job to drive the kids to school in Michael’s car. And that’s what I kept remembering while experiencing this miracle in November that held the geography of so many memories. I recalled driving my siblings to Sacred Heart School (my mom taught at Webb, which was in the other direction.) I used to drive them along Northshore and drop them off at the bottom entrance, and many mornings, my brother Casey, age 11, would begin to plead his case: “Drive us to the top. Drive us to the top. Don’t drop us at the bottom. Please. Please. Come on. It won’t take any longer. DO IT. DO IT. DO IT.”

But I had to be at Knoxville Catholic High School on Magnolia Ave on the other side of town by 8:15 when the bell rang or I got automatic detention. And because getting the four of us out the door (Mom was gone to school already and Dad was long gone to the football office) was a challenge, I always pulled up to Sacred Heart a little before 8:00 AM, so every second counted. Duffy, the other brother, age 15, slept in the backseat in his school uniform and tie, oblivious to all. He didn’t get detention because his football coach was his first-period teacher, and he could sleep through first-period in the Gold Duster in the school parking lot without consequences.

So I would say to Casey, “No. You can walk up the hill. I can’t be late. I have religion class first period. It’s automatic detention.”

“Just do it. Drive us to the top. Drive fast. You’ll make it. Drive us to the top.” Casey didn’t care. He wanted more playground time before the Sacred Heart bell rang.

Keely, the youngest, age 10, didn’t enter the fray, but it stressed her out, and she would get out of the car as quickly as possible and run up the hill.

One morning, things built to a hilt when I dropped them off at the bottom of the Sacred Heart hill, Casey berating me the whole way. He got out of the front seat and pushed his passenger door wide open. Keely had already fled to escape the tension of the car, but Duffy remained blissfully asleep in the back.

I said, “Shut the door, Casey. I’m going to be late.”

Casey said, “No.”

I screamed, “SHUT THE DOOR OR ELSE.”

“Nope.” He danced and laughed. “Ha, ha!”

It was a big heavy door that swung out wide and I couldn’t lean across from the driver’s seat to shut it.

“PLEASE!”

“NO!”

He was calm. He was smiling and then he stuck his round baby face into the car and yelled, “Have a sucky day!”

And he ran up the hill of Sacred Heart laughing, leaving the door wide open.

I wanted to chase after him and throttle him, beat him up - I’d recently learned the word “pulverize” and that sounded good, too, but I had to get to school, which meant I had to get out of the car, walk all around it, and slam that heavy door shut.

Seething, I drove past Lakeshore Mental Hospital (a mental hospital then), and a man we called “Johnny Bench” waved at me like he always did. I waved back, feeling bad for him. We called him Johnny Bench because he was always outside sitting on a bench behind the iron gates of the Lakeshore Mental Institute. For some reason, it calmed me down seeing Johnny Bench sitting here, waving, like life was normal when it felt like anything but in those days.

Thanksgiving Miracle

Steeped in those scenes of wild chaos in the present-day miracle, it looked like my college roommate, Nicki, was going to be okay after all. We’d all gathered around her hospital bed the week before Thanksgiving, and we thought we were gathering to say goodbye. She’d mostly lost the ability to speak, to walk, and to control any bodily function. She recognized us, smiled at us, and didn’t seem surprised we were all there. She later told us she thought we were all living in the dorm again and about to go on a trip together.

Nicki had been in decline for six months, and Kiffen and I had visited in September to take her to see “Knoxville,” a musical based on James Agee’s A Death in the Family, in an adaptation of which I’d played Great-Great-Grandmaw at the Bijou Theatre in Knoxville in the ’80s. It took 90 minutes to get me into makeup (McDonald’s napkins and latex and paint) for my three minutes on stage to say the words, “I been borned again” hugging my great-great-grandson, Rufus.

Agee wrote that Great-Great Grandmaw had “eyes like pieces of broken glass.”

Anyway, we took Nicki to see the play, since I dragged her to so many plays, and we spent the evening together and had lunch the next day on Market Square. She held on tight to me so she wouldn’t fall and spoke in a muted tone that expressed a deep lack of interest in anything.

It was like she was behind a curtain or underwater, and I couldn’t reach her.

Valerie, our other friend, took Nicki to see her favorite band “Air Supply” in September and was shocked at the decline from September to November. I was amazed that Air Supply was still around, and I asked Valerie how they were, and she said, “Like you would expect a bunch of mid-sixty rockers to be. Lotta gray hair, but they could still hit the high notes.”

Still, all fall, Nicki kept getting worse, and they didn’t know if it was early onset dementia, ALS, or a brain tumor. Debby, Nicki’s wife, kept us up-to-date on everything, and finally, they figured out it was Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus.

In September, Nicki had said, “It might be that, but don’t look it up. It’s too awful.”

Of course, I looked it up, and here is the definition:

So we got there on a Friday, and on the Monday before Thanksgiving, they put a shunt in her brain, and on Tuesday, we were driving to visit her and my phone rang, and it was Nicki and when I picked up, she asked, “Could you do me a favor?”

What? Nicki was talking normally?

“Nicki?”

“Yeah, who else would it be? It’s not Debby.”

“You’re okay?”

“I’m hungry. Could you pick me two Taco Supremes, make that three Taco Supremes, from Taco Bell, with extra sauce and some french fries?”

“Yes, yes, of course, I can. You’re okay?”

“Apparently, I’m a Thanksgiving miracle.”

Later somebody said, “We’re calling you Lazarus, Nicki. You don’t even know. YOU DON’T EVEN KNOW.”

The morning of her surgery and so many days that week, we gathered. Pattie, Judy, Jody, Valerie, and so many of Nicki and Debby’s dear friends, and we waited and waited to see what would happen and made plans.

Judy was going to call the Mayo Clinic.

Somebody else was going to call Vanderbilt.

Everybody was trying to figure out how to help Debby who’d been in such tremendous fear and worry for months as Nicki’s beloved wife and caregiver.

(Mrs. Murphy’s Irish rosary for Nicki from Pattie)

Blueberries

But at some point, I knew Nicki was in there when Debby said, “Kerry, take the blueberries home with you.”

I said, “You don’t want them?”

Debby said, “Take them.”

So I took them and I heard Nicki barely above a whisper say to Debby, “You sure didn’t have to ask her twice.”

I laughed and said, “Nicki! You’re in there, aren’t you?”

And Nicki smiled.

Debby also explained, “Danny from the Partridge Family has it,” and of course, I looked that up and he’s doing fine too.

Danny Bonaduce’s Mysterious Illness Explained.

Nicki

And that’s what I was thinking walking around Lakeshore Park, remembering the days of high school, the voices of my younger siblings at the scorching tribunal Sacred Heart drop-off, and in the November light of it all - Nicki being okay.

The sun was shining, and we were walking the dogs around Lakeshore Park, no longer a mental institution, no more Johnny Bench, the gold-red-yellow leaves still on the trees. It wasn’t quite Thanksgiving, and I was in Knoxville, a place of so much grief and loss as a teenager with Michael and now I got to keep my college roommate a little longer.

Mom

So decades later I was given a miracle, and every time I talk to Mom these days, she says, “I’m teetering on 90 I’ll have you know! That is terrifying! Can you imagine? I can’t imagine! How is Nicki? My God, you girls. You girls were given a miracle. You need to write about the miracle.”

Marcesence

I learned a new word recently. Marcesence. It’s when the leaves stay on the trees even in winter, clinging to them, and they only fall off when the spring buds burst through and push them off. Janice, one of the directors of Wild Alabama, said that in spring you’ll see a blanket of beautiful fall leaves floating along the rivers in Bankhead National Forest.

I think that’s what I’ve been doing all my life. Clinging, holding on, not letting go. Part of it was out of pure defiance when my father, the football coach eager to get on the road, not one for “high drama,” spoke in a mighty decree before each dreaded move to a new football town, “Hell, you won’t even remember these people. Say goodbye! We got ballgames to win! Get your ass in the car now!”

And I vowed to remember, crying into the neck of black lab, Clancy, staring out the back window at the town we were leaving behind.

My son, Flannery, read my Substack on Nicki and called me when I was at VCCA in Virginia in December and said, “That’s the best thing you ever wrote, Mom.”

That’s kind of a miracle too - Flannery reading my Substacks. I don’t know where or how he lives, but he reads my Substacks.

Nicki is his godmother.

“Madden is a bitch”

Mom describing her first teaching job at Sacred Heart before she accepted the job at Webb School.

I love this so much! I don’t know any of them but you made me smile, laugh and feel like I do know them. I also love the Knoxville locations as I have been to nearly every one of them. Beautiful writing and yes! A miracle indeed!

Kerry! I completely forgot about Johnny Bench! My grandparents lived on Keller Bend and our parents had moved us when I was 7 from their land to a subdivision in Blount County, so I saw Johnny Bench every Sunday on the way home from Sunday dinner! I am so glad Flannery is reading you! And so happy for your friend.